Adequate equivalence relation

In algebraic geometry, a branch of mathematics, an adequate equivalence relation is an equivalence relation on algebraic cycles of smooth projective varieties used to obtain a well-working theory of such cycles, and in particular, well-defined intersection products. Samuel formalized the concept of an adequate equivalence relation in 1958.[1] Since then it has become central to theory of motives. For every adequate equivalence relation, one may define the category of pure motives with respect to that relation.

Possible (and useful) adequate equivalence relations include rational, algebraic, homological and numerical equivalence. They are called "adequate" because dividing out by the equivalence relation is functorial, i.e. push-forward (with change of co-dimension) and pull-back of cycles is well-defined. Codimension one cycles modulo rational equivalence form the classical group of divisors. All cycles modulo rational equivalence form the Chow ring.

Contents |

Definition

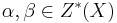

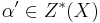

Let Z*(X) := Z[X] be the free abelian group on the algebraic cycles of X. Then an adequate equivalence relation is a family of equivalence relations, ∼X on Z*(X), one for each smooth projective variety X, satisfying the following three conditions:

- (Linearity) The equivalence relation is compatible with addition of cycles.

- (Moving lemma) If

are cycles on X, then there exists a cycle

are cycles on X, then there exists a cycle  such that

such that  ~X

~X  and

and  intersects

intersects  properly.

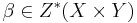

properly. - (Push-forwards) Let

and

and  be cycles such that

be cycles such that  intersects

intersects  properly. If

properly. If  ~X 0, then

~X 0, then  ~Y 0, where

~Y 0, where  is the projection.

is the projection.

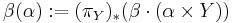

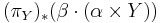

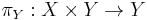

The push-forward cycle in the last axiom is often denoted

If  is the graph of a function, then this reduces to the push-forward of the function. The generalizations of functions from X to Y to cycles on X × Y are known as correspondences. The last axiom allows us to push forward cycles by a correspondence.

is the graph of a function, then this reduces to the push-forward of the function. The generalizations of functions from X to Y to cycles on X × Y are known as correspondences. The last axiom allows us to push forward cycles by a correspondence.

Examples of equivalence relations

The most common equivalence relations, listed from strongest to weakest, are gathered below in a table.

| definition | remarks | |

|---|---|---|

| rational equivalence | Z ∼rat Z' if there is a cycle V on X × P1 flat over P1, such that V ∩ X × {0} = Z and

V ∩ X × {∞} = Z' . |

the finest adequate equivalence relation. "∩" denotes intersection in the cycle-theoretic sense (i.e. with multiplicities). see also Chow ring |

| algebraic equivalence | Z ∼alg Z' if there is a curve C and a cycle V on X × C flat over C, such that V ∩ X × {c} = Z and

V ∩ X × {d} = Z' for two points c and d on the curve. |

strictly stronger than homological equivalence, see also Néron–Severi group |

| smash-nilpotence equivalence | Z ∼sn Z' if Z - Z' is smash-nilpotent on X, that is, if  ∼rat 0 on Xn for n >> 0. ∼rat 0 on Xn for n >> 0. |

introduced by Voevodsky in 1995.[2] |

| homological equivalence | for a given Weil cohomology H, Z ∼hom Z' if the image of the cycles under the cycle class map agrees | depends a priori of the choice of H, but does not assuming the standard conjecture D |

| numerical equivalence | Z ∼num Z' if Z ∩ T = Z' ∩ T, where T is any cycle such that dim T = codim Z (so that the intersection is a linear combination of points) | the coarsest equivalence relation |

Notes

- ^ Samuel, C. (1960), "Relations d'équivalence en géométrie algébrique", Proc. ICM 1958 (Cambridge Univ. Press): 470–487

- ^ Voevodsky, V. (1995), "A nilpotence theorem for cycles algebraically equivalent to 0", Int. Math. Res. Notices 4: 1–12

References

- Kleiman, Steven L. (1972), "Motives", in Oort, F., Algebraic geometry, Oslo 1970 (Proc. Fifth Nordic Summer-School in Math., Oslo, 1970), Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, pp. 53–82, MR0382267

- Jannsen, U. (2000), "Equivalence relations on algebraic cycles", The Arithmetic and Geometry of Algebraic Cycles, NATO, 200 (Kluwer Ac. Publ. Co.): 225–260